1909-2001

The name of Brenda Jones is not now well known outside of her home State but she was a driving force of bridge in Tasmania over four decades. Her story encompasses the transition of bridge from a recreation to a competitive sport and shows what was involved in keeping competitive bridge alive with a small population base.

Brenda was born in Hobart in 1909. Her father John Peters Piggott was a self-made man who had left school at 12 to work as a telegraph boy to support his widowed mother and younger sisters. He educated himself through night school and rose in the public service; and then helped set up the Port Huon Fruitgrowers Cooperative Association, of which he became Managing Director. His business interests eventually extended into jam manufacture, cool stores, export and insurance. Known as a “forceful and gregarious man”, in 1922 he was elected as the National Party member for Franklin in the Tasmanian House of Assembly.

There is sometimes controversy now about politicians involving their children in politics but this is nothing new. JP Piggott would put on a concert featuring members of his family to help attract the crowds – with Brenda, his oldest child, as a singer. He was President of the Chamber of Commerce and heavily involved in various Boards and church and community activities. He was a prominent figure in national debates and organisations related to fruit growing, particularly debates about government support for the industry at the start of the Great Depression.

When Brenda was eight, the family moved from North Hobart to the elite Sandy Bay suburb. (Ironically the end of her bridge career was marked by a move by the Tasmanian Bridge Association (TBA) in the opposite direction.)

Brenda went to Hobart Ladies College where she excelled academically and was Dux of the school. This though was not intended to lead anywhere except a suitable marriage. A career was unthinkable and most temporary paid employment would have been regarded as unacceptable. For a while after she graduated the school employed her as a sports teacher, the only paid employment she ever had.

Like most women of her social class, Brenda would have learned auction bridge as an essential social accomplishment. In Hobart , as elsewhere, a bridge party was a popular form of entertaining or raising money for charity. The first known instance of her involvement with bridge comes from a mention in the social columns that she had hosted a table at a major charity bridge night in June 1928. However, she was not a regular at these events and her main interest at this time was in tennis.

She was a very good player. In 1926 she won the Tasmanian schoolgirls tennis title and two State-wide handicap competitions. In 1927 she made her first appearance for Tasmania in the Ladies Team in the National Championships in Victoria. In 1928, she was the runner up in the State Ladies Championship where the slightly built Brenda was outmuscled by her opponent. Typical of her tenacity, the Illustrated Tasmanian Mail reported that “Miss Piggott proved a plucky and capable little opponent in the final and had her shots carried some of the sting of Mrs Bond’s, the results would have been closer. “As a consolation, though she won (with a Miss P. Jillett) the Ladies Doubles Title. She represented Tasmania in the Melbourne championships again in 1928 and during these years was an automatic selection for the Southern Tasmanian team in the annual contest against the North.

She never completely lost her love of sport and even when heavily involved in bridge, she was a leading female golfer and captain during the 1950s and early 1960s where she displayed the same approach as she did to bridge.

In 1930 her parents took her to England. On the voyage to England , she was on the same ship as the Australian cricket team and got to know Don Bradman, then also a twenty-one year old, well. They kept up correspondence for many years after and in later years the Don sent her an extensively inscribed copy of his autobiography. Once in England , she entered the social round to the extent required and was presented at court but it is likely that her real motivation for the trip was tennis. Today there are records of only one event in which she was entered – the Frinton Tournament – which at the time was second only to Wimbledon in prestige and attracted the best English players. Brenda won through to the second round with a straight sets win. It is not known how much further she got but the place or the event clearly made a big impression as she later named her house ‘Frinton’.

When marriage came, it was to Douglas Jones, the youngest son of Sir Henry Jones, the founder of the IXL fruit processing empire – one of the wealthiest, if not the wealthiest family in Tasmania at that time, and a major employer through its Hobart jam factory (now converted to the Henry Jones Art Hotel). Douglas was Managing Director of W.D. Peacock and Sons (which was an arm of Jones & Co) and was also the agent for the Port Line Shipping Company. On their marriage, the home called ‘Frinton’ was built for them in Sandy Bay. This was much used for entertaining and was not frugal living. Brenda had the services of maids, gardener and butlers as required and furnishings especially ordered from England. This was still an era to some extent of family retainers. When Lady Jones died in the early 1950s, her maid came to live and for lifetime employment to Brenda’s house.

Brenda had three sons Peter, Phillip and David between 1934 and 1942 to whom she was an indulgent mother and a feared and forceful advocate on their behalf, particularly if school wished to do something that might interfere with the boys’ involvement in sport.

Brenda had three sons Peter, Phillip and David between 1934 and 1942 to whom she was an indulgent mother and a feared and forceful advocate on their behalf, particularly if school wished to do something that might interfere with the boys’ involvement in sport.

Probably because of the small population, Hobart did not see the establishment of numerous bridge clubs in the 1920s and 1930s as was the case in the larger states. Previously existing clubs, such as the Victoria League, the Queen Mary Club or the Hobart Yacht Clubs ran bridge sessions but there was no inter-club competition and, prior to 1928 no place where people could gather around the sole purpose of bridge.

The Tasmanian Bridge Association (TBA) was established in 1928 initially at the home of Geoffrey (later Sir Geoffrey) Walch and his sister Marjorie. No records remain of its early history but for its first thirty years it held one session a week in a room at Hadley’s Hotel, the then pre-eminent hotel in Hobart. From there, it moved to a room in the Queen Victoria League building in central Hobart.

Brenda’s first appearance as a Tasmanian representative and TBA member was in 1950 at the Hobart ANC when she captained the women’s team, making it likely that she had been playing with the Association for some time in the 1940s. She was not selected in the 1948 and 1949 teams but it is not clear whether this was because of her state of progress or was simply because she was unable to travel in those years, because of other commitments or other reasons.

For the next thirty years, she dominated bridge in Tasmania. When people speak of her now, they say she “was the TBA”. She represented Tasmania on many occasions. She was captain of the Women’s Team in 1950, 1953, 1956, 1960 and 1973, and a member of the team in 1971, 1972, 1974-76, 1978, 1980 and 1984-85. She was captain of the Open Team in 1951 and a member of the Open Teams of 1966, 1967, 1968 and 1977. It has to be said that, during this period, she usually chose the teams (she effectively was the Match Committee) – but she would in any case have been an automatic choice. She would not be considered a great player but she was respected as a good player in good company.

Prior to the mid-1960s, Tasmania did not always send teams or a full complement of teams to the ANC. This was not due to a lack of interest but, as Brenda explained to ABF councillors, the difficulty of finding enough people with the necessary skill who were in a position to take time off for the contest. The composition of the teams shows an interesting aspect of early bridge in Tasmania – particularly the prominent role taken by female players. In the 1938 Hobart ANC, which was the first time Tasmania competed, the captain of the Open Team was Mrs G. Martin, with three male colleagues. (The division between Open and Women’s Teams in this year was decided by geography. Launceston and the North provided the Open Team and Hobart the Women’s.)

In 1948-1950, only women’s teams competed. In Melbourne both Open and Women’s Teams competed but the Open team consisted entirely of female players (with Brenda as captain). In 1953 and 1958 only women’s teams competed. In 1954, the Open Team was captained by Mrs C. Boag, one of the leading figures in the Tasmania Bridge Association since the 1940s. It was not until 1960 when women disappeared from the Open Team. Mrs Boag was the first female tournament director of an ANC (in 1950).

Much of this reflected the way in which Brenda drove to keep duplicate bridge alive and flourishing in Tasmania. Given the population size – Greater Hobart had less than 100,000 people in the early 1950s – this was no easy task. More than in other capitals, the viability of duplicate bridge depended heavily on recruiting substantial numbers of people who in the normal course of events would have been happy to stick to social rubber bridge.

She kept membership alive by two main tactics – incessantly badgering people she knew (and she knew a lot of people) to join and teaching. “No” was not an answer she accepted when inviting people to join – she had no time at all for rubber bridge. Several people commented that she left them absolutely no peace until they agreed to join. She emphasised that to keep bridge alive you had to teach. She was a very good teacher – you failed to pay attention at your own peril. She was also instrumental in pushing for the teaching tours by Ron Klinger to be extended to Tasmania (and Ron would stay with her when he visited.

She was either President or Secretary until the mid 1980s; was the Tasmanian representative at the Australian Bridge Council (ABC) and its successor the ABF from 1950 to 1983. In 1960, she was the first female Chair of the ABC when the responsibility for Council administration rotated to Tasmania. In the 1950s and 1960s (as was also the case with Western Australia ), mainland proxies often acted for Tasmanian representatives – Frank Cayley often took the role of Brenda’s proxy. From the late 1960s she attended more or less continuously until her retirement in 1983.

As an ABF Councillor, Brenda’s combined interest in strategic organisational issues as well as the minutiae of bridge. Her main interests were promotion and financing. To some extent the issues were linked. To put the ABF in a stronger financial position (and in the process reduce the relative burden of Tasmania), she several times proposed in the 1970s that each bridge club member in Australia be made a member of the ABF through a small addition to club membership fees.

Among other things, she hoped that the increase in revenue would allow the ABF to provide enough support to keep Australian Bridge afloat. She felt that “as a first rate publication, appealing mainly to the more dedicated players, I cannot see it ever paying its way” and that the only long-term solution would be for the ABF to take responsibility for it.

When others did support the thrust of her directions, she wanted to make sure it was done properly. When it was agreed that a national Promotion Officer be appointed, she asked Councillors “to think clearly before fixing a salary for a Promotion Officer. Do not put the cart before the horse – first ascertain the ultimate duties of such an officer.”

Her suggestions for suitable promotion schemes included free bridge courses in schools, school holiday seminars, promoting bridge as a way of raising money for charities, taking it to institutions such as gaols, rehabilitation homes and “blind, deaf and dumb” institutions, approaching large country-based organisations such as the Country Women’s Association and promoting bridge in over 60s clubs.

She was conscious that money for this had to come from somewhere and in addition to her new financing scheme, was prepared to argue for shifts in priorities. She commented that “the A.B.F. seems to have inexhaustible funds to distribute loans and remunerations. I firmly believe that the A.B.F. should halt and take stock of its assets and expectations of future monies needed for teams, etc.”

Conscious as she was of the importance of social events though, she was very clear that the aim of the ANC was to provide opportunities to play with top players as much as possible. In the lead up to the 1973 ANC she was aligned with Keith McNeil in a failed attempt to reverse an ABF decision to reduce the number of hands to be played.

In 1975 Brenda became Tasmania ‘s first weekly bridge writer, with a column in the Saturday Evening Mercury. The newness was illustrated by the fact that the early diagrams were copied handwritten ones. She continued the column until 1982. The column also illustrates the growth of bridge in Hobart during her long Presidency. The first column explained what duplicate bridge actually was and recorded the results from a single movement. The last column showed bridge was being played three nights a week with multiple movements.

The urge to spread bridge was not at all costs. Most club members of the 1950s and into the 1960s, including Brenda, wanted new members but also believed in standards of dress and behaviour. Evening dress for evening bridge sessions was common in all States in the 1940s and earlier. At the 1948 ANC, it was agreed that players be informed that evening dress was desirable (although not compulsory) for evening sessions. A strong dress code probably was sustained longer in Tasmania than elsewhere. TBA sessions in the 1950s basically required full evening dress and Brenda maintained high dress standards (although not necessarily evening dress) as long as she could. Some female members would have a selection of hats specifically for bridge nights. Where there was a conflict between standards and expansion, standards came first. She basically exercised a right of veto over membership. University students and other undesirables not dressed to the appropriate standard could not expect to be allowed to play.

The emphasis on dress was not though the same thing as stuffiness. She was a critic of the practice of finishing the ANC with a relatively expensive formal dinner. If the formal dinner were to continue she suggested that “the young participants in the ANC and Congresses should be allowed in, providing properly attired, to the presentation of prizes, and dancing. It seemed a pity to waste good music.” Ever businesslike, she added that “if necessary they could pay for the privilege”.

Brenda’s time as an ABF Councillor ended in 1983 and was a time of both physical and generational change for the TBA. She was made a life member of the TBA and included in the ABF’s Committee of Honour in recognition of her long contribution. She was succeeded as councillor by the young Hugh Grosvenor and the TBA moved to its own premises in North Hobart, in the process weakening the Sandy Bay connection.

Brenda’s husband died in 1994. Although very frail, she remained intellectually alert and managed to live on her own until her death in 2001. She continued to play bridge until she was ninety and continued to do some teaching well into the 1990s. She bought a computer a couple of years before her death. Absolutely determined not to enter a nursing home, she developed a comprehensive network of family and friends who provided the different types of support that she needed. One time in her nineties, she was fully reclined in an electrically operated armchair when the power failed. She was not distressed and in her normal manner simply dialled, as you do, the police who came and lifted her up.

Brenda’s husband died in 1994. Although very frail, she remained intellectually alert and managed to live on her own until her death in 2001. She continued to play bridge until she was ninety and continued to do some teaching well into the 1990s. She bought a computer a couple of years before her death. Absolutely determined not to enter a nursing home, she developed a comprehensive network of family and friends who provided the different types of support that she needed. One time in her nineties, she was fully reclined in an electrically operated armchair when the power failed. She was not distressed and in her normal manner simply dialled, as you do, the police who came and lifted her up.

Both Brenda’s younger brothers went on to successful careers, one as a prominent lawyer prominent in a wide range of community activities and legal and international societies; and the other a major figure in insurance industry. Her youngest brother, John Bruce Piggott, mused in his autobiography about what Brenda might have been able to achieve in different circumstances:

“Mother wanted my elder sister to marry well, since that was considered the most desirable course for girls in those days. I have often wondered how far my sister Brenda would have gone had she sought a business or political career, either in addition to or instead of marriage, because she was and is in every respect a leader. She has a good intellect and a strong personality, boundless energy and much determination. She chose a marriage which was a successful and happy one, to the youngest son of Sir Henry Jones, my father’s ultimate rival in business.But she ‘revenged’ herself on my parents and her two brothers by bossing them for the rest of their lives. She may not have gained power in business or politics but she ruled, she ruled just the same, in everything else.”

Hardly anybody who remembers Brenda did not use the description of “bossy” at some point – but she generated relatively little resentment and was most commonly held in high regard by members. It was usually recognised that her motives were completely selfless. She was regarded as a good partner apart from her addiction to trap passes. The teacher in her would have regarded not telling a partner where they had gone wrong as an abdication of responsibility but she is remembered as somebody who could do this in a way that was never felt as belittling. Beneath the bossiness, she was regarded as a good friend, a person with a great sense of humour and a good source of sensible advice.

Hardly anybody who remembers Brenda did not use the description of “bossy” at some point – but she generated relatively little resentment and was most commonly held in high regard by members. It was usually recognised that her motives were completely selfless. She was regarded as a good partner apart from her addiction to trap passes. The teacher in her would have regarded not telling a partner where they had gone wrong as an abdication of responsibility but she is remembered as somebody who could do this in a way that was never felt as belittling. Beneath the bossiness, she was regarded as a good friend, a person with a great sense of humour and a good source of sensible advice.

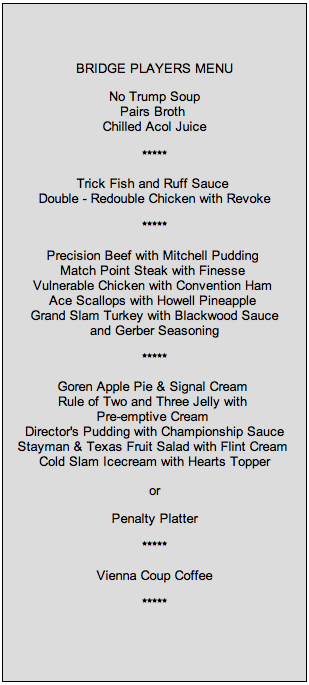

Brenda was heavily involved in the organisation of the 1950, 1960 and 1973 Hobart ANCs. The events were smaller and more personal then. Brenda’s social status gave a lot of prominence to the events. For the early ANC there was a Lord Mayor’s reception for the players and it was de rigueur for the host bridge club members, including Brenda who hosted the 1960 and 1973 event, to hold receptions for the interstate players in their homes with full buffet. The social events organised for the visiting players featured prominently in the social pages of the Mercury. Brenda always understood the importance of fun and social gatherings as shown by the menu on the left that she designed for the TBA’s 50th anniversary dinner.

History has not been particularly kind to the era when society women, such as Brenda, dominated the numbers at the bridge table. The social aspects are real enough and the dress and other standards that went with it undoubtedly excluded many. It could not continue. Nevertheless, a lot of intellect and drive was brought to the table that was not light weight in any way and did much to laying the foundations for the established state of bridge today.

Acknowledgements

This article depended very heavily on many Tasmanian bridge players who had personal memories of Brenda, including Sheila White, Joyce Burrows, Angela Little, Barbara Hammond, Bert Forage, Bruce Williams, Kalev Krupp, June Gibson, Peggy Whenn and Yvonne Barnes.

Sue Wilkinson and Dallas Cooper of the Tasmanian Bridge Association were extremely helpful in finding the records that were available and suggesting people to talk to. Ian Sandercock unearthed some of Brenda’s articles in the Saturday Evening Mercury.

David and Lindy Jones (Brenda’s son and daughter-in-law) provided the photographs and much useful family history. John Bruce Piggott’s autobiography, Reflections of A Common Attorney was the source of the remainder of the information on John Peters Piggott. Information on Brenda’s early tennis exploits came from reports in the MelbourneArgus (via the National Library’s digitalised collection) and the Illustrated Tasmanian Mailof 1928.